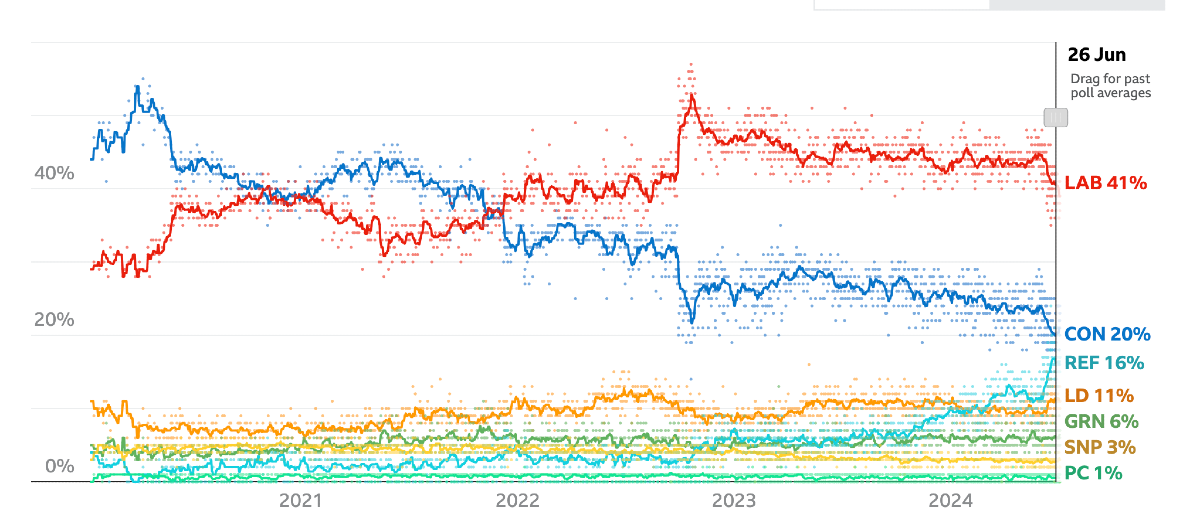

Election 2024: Growing Political Distrust

Political distrust is at an all-time high, and it’s reshaping the electoral landscape in unsettling and unpredictable ways.

Political trust is generally high when people have confidence in their government and political leaders, and view them as trustworthy, fair, credible and competent. In Western democracies, politicians have tended to be more distrusted than trusted. Some experts argue that this “liberal distrust” is a good thing as it ensures accountability through an ongoing evaluation of the performance of political leaders. Some have even referred to this liberal distrust as the ‘guardian of democracy’. However, what we’re seeing now in the UK is a deeper and more concerning level of political distrust.

Bertsou argues it is important not to conflate "liberal distrust" with political distrust, which, far from being beneficial, is a potentially damaging and destabilising force. He argues that political distrust is not merely a lack of trust where there is doubt and scepticism about the government’s intentions but a strong and settled belief in the untrustworthiness of political leaders. Hence, once the public becomes distrustful of a government or politicians more generally, it is hard to reverse this view.

There are three aspects to political distrust according to Bertsou. The first is based on evaluating the competence of political leaders and government. The second is based on unethical and untrustworthy conduct, which the public sees as wrong or unfair. Public perceptions of untrustworthiness, corruption, bribery and cronyism are all strongly associated with political distrust. The third is based on partisanship, where people are more likely to distrust politicians they disagree with. Bertsou argues that distrust which stems from the betrayal of a previously extended trust, can carry a strong moral judgement.

Political trust has been declining in the UK for several decades. This has been attributed to political scandals, such as the MPs expenses scandal in 2009, and the increasing prominence of cynical views about politicians. In 1986, 40% of people trusted the government to place the nation’s needs above the interests of their party. By 2010, this had halved to 20%.

(See

NatCen report.)

The British Social Attitudes Survey

2023 report found that “people’s trust in government and politicians, and their confidence in their systems of government, is as low now as it has ever been over the last 50 years, if not lower.” The report argued that the actions of the Conservative government, particularly contravening its own rules on COVID-19, had a corrosive effect on public trust. By August 2022, 76% of the public felt Boris Johnson was untrustworthy. While the figures improved for Rishi Sunak, two-thirds of the public (65%) believed he was untrustworthy.

The percentage of people who trust the government to place the nation's needs above their party most of the time fell from 24% in 2021 to 14% in 2023. More dramatically, the percentage of the public that trusted politicians to tell the truth in a tight corner fell from a low of 12% to just 5%. (See

NatCen report.)

A 2023

Ipsos survey found that people's trust in politicians had fallen to its lowest level in 40 years. Just 9% of people said they trusted politicians to tell the truth, making them the least trusted profession in Britain. According to Ipsos, almost all of the decline in trust in Britain’s politicians over recent decades had come about during the Conservative Parliament of 2019 to 2024.

In 2024, Ipsos conducted a study called ‘The People Behind the Polls’, where they followed a group of people during the 2024 election campaign and obtained their reactions to events such as the TV debates. This qualitative research survey found that the public had a “complete distrust of politics and politicians.”

An

analysis of the British Election Study panel in 2024 found that over 70% of those aged 18-60 agreed that ‘politicians don’t care what people like me think’. The figure was 76% for respondents aged 30-44.

After participating in numerous focus groups the pollster, Luke Tryl, has claimed the public overwhelmingly distrust politicians of all parties. They either think they are not up to the job or are only in it for themselves. He believes the notion that there is one rule for politicians and another for other people “is toxic not just to one party but faith in politics itself.” (See Luke's posts

here and

here.)

The

41st British Social Attitudes Report published on 12 June 2024 reported that public trust in government has fallen further to a new record low. Almost half of people said they would ‘almost never’ trust British governments of any party to place the country's needs above the interests of their own political party, more than ever before.

When non-voters were asked why they didn’t vote in 2024, the top answer selected by 34% was ‘I don’t trust any politicians’.

When Keir Starmer became Labour leader, most of the public (59%) had no view on his trustworthiness, and only 19% distrusted him. However, the more the public got to see Starmer, the more they distrusted him. When it was revealed that Sue Gray had been offered a job as Labour’s chief of staff, the percentage of the public who believed Starmer was untrustworthy jumped from 38% in April 2023 to 45% in May 2023. In September 2024, after a difficult summer, 47% believed Starmer was untrustworthy.

The Consequences of High Levels of Political Distrust

Higher levels of voter distrust can lead to more unstable electoral environments. Research by

Voogd et al., published in 2019, found evidence that low levels of trust undermine the formation of stable party preferences and stimulate volatility. They discovered that declining trust drives voters, particularly supporters of parties in government, to change their party preference. High levels of distrust also create opportunities for populist parties, which appeal to voters with simple solutions on the basis that the political and establishment elites cannot be trusted.

High levels of distrust can also lead to unpredictable behaviour where voters seek to punish existing political leaders by acting or voting in a contrary manner to register a protest against the existing government. Research by

Okolikj et al. found that voters with high levels of distrust were more likely to vote for protest parties, even if such parties were far removed from their own ideological position, to express their distrust of politicians.

Distrust can also lead to people opting out of the political system, which can be reflected in low levels of voting and political engagement. The

2020 British Attitudes Survey found that turnout in the 2019 election was lower among people who said they almost never trusted the government. The same survey also found that 62% wanted a change in the current voting system and were “markedly more likely to have a populist outlook.”

In summary, the growing levels of political distrust in the UK over the last decades have increased the potential for electoral volatility, including greater polarisation (Boxell et al. 2020), support for populism (Henley 2018), and a decline in political participation (Repucci and Slipowitz 2021). In 2021, the IPPR warned that this growing distrust “can lead to a downward spiral of democratic decline, with voters disengaging, becoming polarised, or turning to populist leaders and causes."

My latest book Collapse of the Conservatives : Volatile Voters, Broken Britain and a Punishment Election is now available on Amazon.