Blog Articles

In the 2024 general election the 18-24 year-old age group was the only age group where the two main parties combined received less than fifty-percent of the vote. 19% of this age group voted for the Greens while 8% voted for Reform. It was the latest sign of young people’s increasing unhappiness with the current political and economic situation. Their feelings of relative deprivation compared to previous generations appears to be driving young people away from the mainstream parties and towards more radical parties. I first studied relative deprivation theory at university back in the 1980s. It was used to describe feelings of individuals or groups where their sense of economic, political, or social deprivation was relative rather than absolute. In the 1970s research by Crosby and others found that people made judgements of fairness by comparing how they were treated and what they had in comparison to other people or groups rather than in absolute terms. They therefore felt relatively deprived if what they had differed from what they believed they ‘ought’ to have. This relative deprivation gap, whether perceived or real, gave rise to feelings of anger, betrayal and unfairness. Further research by Ted Gurr found that these feelings often gave rise to anger and aggression. While relative deprivation typically involves a comparison of present circumstances with others, ethnographic research has found that people increasingly make comparisons with the past and previous generations. (Cramer, 2016; Gest, 2016; Kuisz & Wigura, 2020). This has been termed ‘nostalgic deprivation’ where people feel their current status has declined relative to their perceptions of the past. Research by Gest et al, in 2018 found that support for Donald Trump and the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP) could be explained by nostalgic deprivation. This group-based nostalgia deprivation can create a sense of downward mobility. These perceptions of declining status appear to be a consistent predictor of support for populist and radical parties in Europe (Ferwerda et al, 2024). Research by Gest et al (2018) found that ‘nostalgic deprivation’ explained radical right voting better than absolute economic deprivation. Research by Kurer and van Staalduinen in 2022 found that nostalgic deprivation didn’t simply apply to ethnic, geographical, social or cultural groups but also to different generational groups. When young people sought to understand their current status relative to the past, they frequently looked to their parents as the reference group in order to make comparisons. Research by Bolet in 2022 also found that younger Europeans who perceived their social status to be lower than their parents felt that prospects for ‘people like them’ were declining and had a strong sense of nostalgic deprivation. Researchers further found that younger voters who viewed their educational and occupational situation unfavourably to that of their parents were more likely to support populist parties. In the UK it is not hard to see why younger generations might feel relatively deprived. Back in 2015 the UK Parliament Select Committee on Work and Pensions noted there was “abundant evidence” that young workers were “enduring a lower standard of living than today’s pensioners did when they were the same age”. Young people’s earnings are lower than that of previous generations. The typical weekly pay of graduates aged 30 to 34 fell by 16% between 2007 and 2023. The cost of housing is also much higher. Average house prices in the UK are 65 times higher than they were 50 years ago, while wages are only 36 times more. In 1960 the average age of a first-time buyer was 23, it is now 34, and most homebuyers under the age of 35 rely on the bank of Mum and Dad for their deposits. The cost of housing and rising rents means that more young people are living at home and are prevented from moving to areas where there are economic opportunities. The current generation of young people is also burdened by student loans. The UK now has some of the most indebted graduates in the world, with the average student debt being around £50,000. The high level of fees and interest on student loans mean many university students today will pay an extra 9% of their income above the student loan threshold towards the cost of their higher education for most or all of their working lives. Generational feelings of relative deprivation may give rise to growing anger about the political system and may lead younger people to vote against the status quo. They may be less likely to support mainstream parties and instead vote for more radical opposition parties, including populist parties of the left as well as the right. It is time for political parties to address young people’s sense of relative deprivation and to demonstrate that they are taking concrete steps to remove intergenerational inequality. My latest book Collapse of the Conservatives : Volatile Voters, Broken Britain and a Punishment Election is now available on Amazon.

Following her election on 2 November 2024, Kemi Badenoch and the Conservative Party face a number of key challenges: • The Reform challenge • The competence challenge • The narrative challenge • The demographic challenge The Reform Challenge

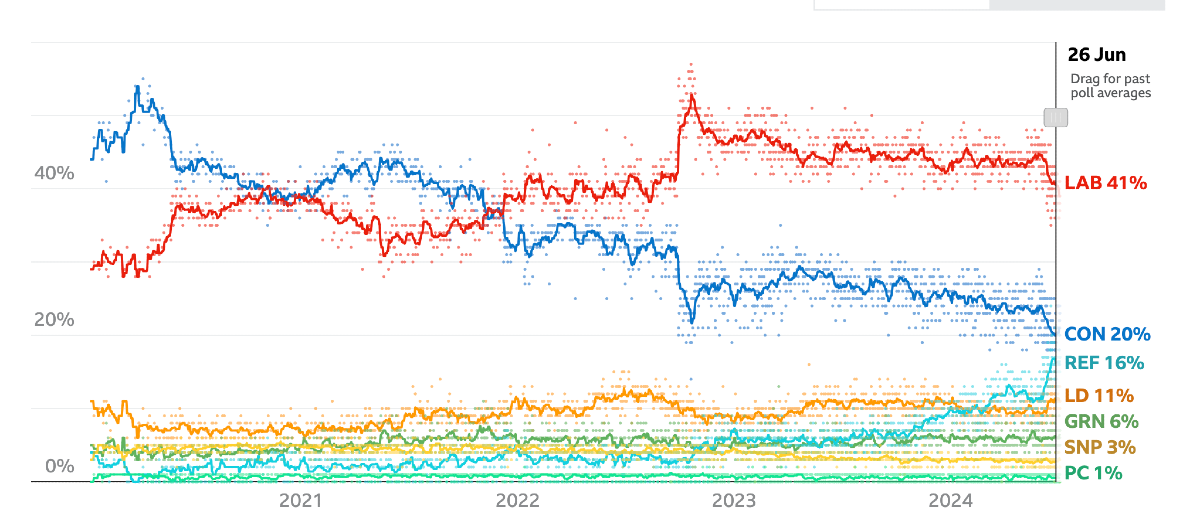

One reason the Conservatives dominated parliament over the last 80 years is that the country’s centre-right vote consolidated behind the party while the centre-left vote was divided between parties, primarily Labour and Liberal Democrats. The rise of Reform fatally divided the centre-right in 2024, making it easier for Labour to win seats from the Conservatives.

The threat from Farage and his colleagues is very real. Nearly a third (29%) of the Conservative Party’s 2024 voters said they had considered voting for Reform, compared to 17% who said they had considered voting for the Liberal Democrats. Kemi Badenoch has said Nigel Farage would not be welcome in the party, saying, “We are a broad church but if somebody says they want to burn your church down, we don’t let them in.”

A YouGov survey after the election revealed that 42% of Conservative Party members would support a merger with Reform, while 51% would oppose such a move. Only 34% of party members felt the party should move to the centre with 51% believing the party should move to the right to attract Reform voters.

However, a survey by Savanta suggests that Tory to Reform switchers are probably the hardest voters for the party to win back. The other problem is that even if the party could win back every vote that went to Reform in the general election and keep all of its 2024 voters, it would still only win 302 seats, which falls short of securing the 326 seats required for a bare majority in parliament. If Reform does become increasingly professional, does more work building a base on the ground in constituencies, and develops a targeted approach to election campaigns, there is a risk that it could become an even greater threat to the Conservatives.

The Competence Challenge After 2016, the Conservative Party lost its reputation for competence and lost the trust of key groups of voters. There is evidence that people primarily broke with the Conservatives over the issue of competence, but where they went depended on their values. So, more authoritarian voters went to Reform, while others went to Labour, the Liberal Democrats, or other parties, and others stayed at home.

A key challenge is how the party rebuilds its reputation for competence while in opposition. Some commentators have argued that voters become frustrated with governments and that if Labour begins to look incompetent, then the Conservatives will appear competent by comparison. Thus, time will solve some of the party’s problems. The difficulty with this argument is that the voters may desert Labour, but they may not return to the Conservatives. They may express their dissatisfaction with the government by voting for the Greens, independents, or Reform.

To rebuild trust and a reputation for competence, the party must be seen to be united under an effective leader. The leadership team also needs to exude capability and integrity. There needs to be a perception of discipline, not one of constant infighting between factions. The party also needs to be honest about its own failings while in government. A 40-page pamphlet promoted by Kemi Badenoch as part of her leadership campaign, Conservatism in Crisis,1 was remarkable in failing to address why the Conservatives lost the election. There was no acknowledgement that the party presided over crumbling public services and was perceived as incompetent. The only reference was to the failure to control immigration; there was not a single mention of competence.

The Narrative Challenge One of the Conservative Party’s key challenges is to define a new narrative or reclaim a previous narrative. Fundamentally, what does the party stand for?

Traditionally, the party has claimed to be the party of sound economic management, and a supporter of the free market, a smaller state, and lower taxes. Following the Truss debacle, it may take some time for the Conservative Party to recover its reputation as economically competent.

If the party is going to advocate for a smaller state, it needs to be clear what this means and the significant reductions in state activity it would like to see. The frequent cries for reductions in foreign aid, fewer regulations, and cuts in funding to arts organisations are too small to make any real difference to the level of state spending. The big spending areas, such as the NHS, schools, and local government, have already been cut heavily, and there appears little scope for further reductions. Indeed, the public in 2024 wanted to see more investment, not less, in these areas while accepting that there could be some scope for greater efficiency. Even the Conservative 2019 voters who defected to Reform wanted to see more investment in public spending and an improved NHS.

It is not clear the Conservatives have yet understood that the electorate is more supportive of state intervention and public services than they are. In her pamphlet, Conservatism in Crisis, Kemi Badenoch argued that what all Conservatives want is “growth, social cohesion, better public services and sustainably lower taxes”. The potential dichotomy of lower taxes and better public services was not recognised. She argues that taxes can be cut significantly while at the same time improving public services. She believes this could be done by reducing regulation, cutting welfare spending, and making cuts in what she terms the bureaucratic class, primarily administrators such as human resources, equalities, and compliance staff.

All of the groups of voters the Conservatives lost in 2024 were to the left of the party on key economic issues, including Reform voters. These voters want to see more public service investment and are not instinctively small-state advocates. The centre-right think tank Onward argues the Conservatives will, therefore, have to craft a strong story that the party can manage and improve public services, particularly the NHS, which will mean a new triangulation around the issue of tax cuts and public spending.

The Demographic Challenge The party’s voting base in 2024 was older than it had ever been. The only age group the Conservatives won in the election was the over-65-year-olds. On current trends, there is a real danger that the Conservative Party will become the pensioner party.

The country’s changing demographics will make it increasingly difficult for the party to win unless they can increase their appeal to younger people. Focaldata has estimated that some 17%, or one in six of those who voted Conservative in 2024, will have died by the time of the next election. That would mean over a million fewer Tory voters lost solely as a result of demography. By contrast, the Labour Party is anticipated to gain the support of 800,000 young people who become legally able to vote before the next election, compared to just 160,000 for the Conservatives. If Labour legislates to grant the vote to 16 and 17-year-olds as they intend, the position is likely to get worse for the Conservatives.

Young people’s perceptions of the Tories declined markedly after Brexit. The percentage of 18 to 34-year-olds saying they strongly disliked the Conservative Party jumped from around 20% prior to the Brexit referendum to over 40% by 2023.

This was the age group that Thatcher successfully appealed to in the 1980s. Her policies, including lower taxes, ‘right to buy’, and the sale of shares in previously nationalised industries, were designed to appeal to young aspirational voters and encourage social mobility. In 1979, 42% of 18 to 24-year-olds and 43% of 25 to 34-year-olds voted for the Conservative Party. In 2024, the party secured just 5% of the votes of 18 to 24-year-olds and 10% of the votes of 25 to 34-year-olds. The party came fifth amongst this younger age group, behind Labour, the Greens, the Liberal Democrats and Reform. The Conservative Party has arguably been too focused on maintaining the support of the older generation of homeowners and become detached from the aspirations and values of the next generation. This matters because the party can no longer rely on the traditional conservatising effect of age, which was observable in previous generations as voters became homeowners, got married, and had children.

Britain’s younger generation overwhelmingly voted for the stability of remaining in Europe and are particularly frustrated at the broken housing market. Like the previous generations, they aspire to own their own homes but find it increasingly difficult as house prices and rents have increased relative to salaries.

The Conservative Party’s problems with younger voters are stark. Sam Freedman has observed that the real challenge for the Conservatives is “finding a way to reconnect with younger and middle-aged people earning, or hoping to earn, decent salaries and own a home”. For the Conservative Party to win again, it needs to find a way to appeal to young, aspirational, and socially liberal voters. My latest book Collapse of the Conservatives : Volatile Voters, Broken Britain and a Punishment Election is now available on Amazon.

In the run-up to the 2024 general election, both Keir Starmer and Rachel Reeves claimed that taxes on working people were at their highest for 70 years . They argued this was an unfair burden and said that unlike the Tories, they would not raise taxes on working people. There was only one problem—the claim was untrue. While the overall tax burden as a percentage of GDP had increased after the Covid-19 pandemic and was at its highest for 70 years, it was not the result of increasing taxes on median earners. The Conservative government had actually managed to reduce the tax burden on average earners to its lowest level in 50 years , and had significantly increased taxes on the wealthy, the highest earners and corporations. An achievement that went largely unreported or commented upon. The UK’s tax revenue was also below the G7 average and considerably lower than most other Western European countries . Paul Johnson of the IFS argued that one of the UK’s problems was that middle earners were actually taxed too little relative to its European neighbours, and the country was too reliant on the taxes of the highest earners. The average tax rate for someone on median earnings in the UK was 28% in 2016/17 compared to 44% for Western European countries. The reality was that taxes on average earners in the UK were low relative to other European countries and had been reduced to their lowest level for five decades under the Conservatives. This was in no small part due to a 4% cut in the main National Insurance rates which Labour supported and promised not to reverse. In 2024, someone on £35,000 a year would pay £2,000 less tax than in 2010 when Labour left government, while someone on £50,000 a year would pay £1,000 less tax. One of my frustrations with politicians of all parties is their refusal to be honest with the public about taxes and spending. I am sure I am not alone in shouting at the radio when a politician says they are spending record amounts of money on the NHS. When the population has risen by 6m since 2010, when the population is ageing and when we have had high inflation in recent years the claim is at best meaningless. If Labour was honest it would say taxes on average earners were reduced to an unsustainably low level under the last government and need to be increased so we can improve public services. It would acknowledge that those with the broadest shoulders have borne most of the burden, the top 1% now pay 29% of all tax, and while the government may be able to squeeze more from them, what is really required is higher taxes on average earners. In reality, the government does, of course, recognise the need to raise taxes on average earners and is committed to freezing the income tax threshold until 2028 which is a major tax increase on working people. The government believes this form of stealth tax increase is more politically manageable than increasing rates of tax. However, the downside of increasing taxes on working people by freezing thresholds is that it hits the young and the poor the hardest. This is because the proportional impact of fiscal drag on the spending power of those on low incomes is greater than that of those on high incomes. The freezing of the student loan repayment threshold is a further burden on young people with loans The Labour Party’s promise not to increase the rates of income tax, national insurance and VAT was based on a demonstrably incorrect claim about the tax burden on average earners, and the consequences will severely limit the Labour government’s ability to raise taxes to invest in public services and support the UK’s ageing population. My latest book Collapse of the Conservatives : Volatile Voters, Broken Britain and a Punishment Election is now available on Amazon..

The increased willingness of voters to vote tactically in the 2024 general election put the Conservatives at risk in a large swathe of seats, which became known as the Blue Wall. This vulnerability became apparent just a month after the Conservatives won the Hartlepool by-election in 2021. On 17 June 2021, the party lost a by-election in Chesham and Amersham, a constituency which had been Conservative since its creation. It was won by the Liberal Democrats on a huge swing of 25 points. The Conservative share of the vote fell from 55.4% to 35.5%. The result was initially put down to local concerns regarding HS2 and the relaxation of planning controls. However, the result was an indication that the Tories were vulnerable to tactical voting in constituencies in traditional conservative seats in Southern England, which had voted against Brexit and were becoming more liberal. Many constituencies in the south have been changing demographically as younger, more liberal graduates move out of London in search of cheaper housing. Mike Martin, the Liberal Democrat candidate in Tunbridge Wells, estimated that around 3,000 people had moved into his constituency every year since 2019. Tony Travers, a director of LSE London, a research centre at the London School of Economics, argued the Chesham and Amersham by-election result was the result of this gradual “erosion of the Tory party’s traditional rock-solid voter base in the south-east of England.” Travers believed that demographic changes were significant, noting that in a typical year, more than 200,000 people move out of London to the south-east and east. Travers argued that Labour votes were effectively being exported to the wider region. As evidence, he pointed to the 2019 local elections, where the Conservatives faced sudden and vast losses of councillors in places such as Chelmsford, Chichester, East Cambridgeshire, Guildford, South Oxfordshire, Vale of White Horse, Winchester, Woking, Surrey Heath and Spelthorne. The day after the by-election, Ed Davey, the Leader of the Liberal Democrats, took an orange mallet to a wall of blue bricks with an orange mallet to symbolise his party's victory. The Guardian used the photo in an article published on 19 June 2021, headed ‘The Blue Wall: what next for the Tories after a shock byelection defeat?’ The article identified 29 Blue Wall seats where the Tory majority was below 30%, the Liberal Democrats came second, and the Leave vote was below 53%. These were: Brecon & Radnorshire Cambridgeshire South Cambridgeshire South East Chelsea & Fulham Cheltenham Chippenham Cities of London & Westminster Esher & Walton Finchley & Golders Green Guildford Henley Hitchin & Harpenden Lewes Mid Sussex Mole Valley Newbury Romsey & Southampton North Somerton & Frome South West Surrey Sutton & Cheam Taunton Deane Thornbury & Yate Tunbridge Wells Wantage West Dorset Wimbledon Winchester Witney Wokingham Steve Akehurst identified a similar group of Blue Wall seats, which were historically Conservative but where he believed the party could lose because of tactical voting. Akehurst specifically identified seats where: Labour or the Liberal Democrats had overperformed their national swing versus the Conservatives in 2017 and 2019. The Conservative majority was under 10,000 votes. A disproportionately large number of residents were graduates. These seats were primarily in suburban areas in England, often on the outskirts of cities or large urban conurbations. Akehurst argued that voters in these seats were more likely to focus on issues like housing and the environment rather than immigration. They were also more pro-EU and liberal than the new Conservative voters in the Red Wall and felt increasingly distant from the Tory Party. There was growing evidence that the 2024 general election could see high levels of tactical voting. A month before the election, one in five voters in a YouGov survey said they would be voting tactically, with three quarters saying they would be willing to do so to stop a Conservative from winning their seat. To cater for these tactical voters, many websites were set up to identify the party best placed in individual constituencies to beat the Conservatives. These included Tactical Voting, Stop the Tories, and Best for Britain. Naomi Smith, CEO of Best for Britain and founder of the tactical voting platform GetVoting.org, claimed that over ten million people were willing to vote tactically for change in 2024 . The increasing willingness of people to vote tactically, combined with the changing demographic nature of Blue Wall seats, made the Conservative Party particularly vulnerable in these constituencies. The 2024 election result The party was devastated in the traditional Conservative home counties’ heartlands. For the first time since 1906, Tories didn’t win a majority of southern seats. In Berkshire, Bedfordshire, Buckinghamshire, Hertfordshire, and Oxfordshire, the party lost 26 seats. Many of the seats the Conservatives lost in 2024 had been held by the party for a very long time: Aldershot (1918) Ashford (1931) Banbury (1918) Basingstoke (1924) Both Bournemouth seats (1921) Bury St Edmonds (1885) Cities of London and Westminster (1931) Chichester (1924) Devon South (1935) Dorking (1885) Henley (1910) Macclesfield (1918) Mid Sussex (1885) Tunbridge Wells (1931) Worthing West (1918) The Liberal Democrats took seats from the Conservatives in some of the country’s wealthiest areas that have the highest proportions of people in managerial and professional occupations. While the Liberal Democrats failed to take the seat of the former chancellor Jeremy Hunt, it won the seats of three Conservative ex-Prime Ministers: Maidenhead (formerly Theresa May’s seat) Henley (formerly Boris Johnson’s seat) Witney (formerly David Cameron’s seat) The success of the Liberal Democrats in winning 72 seats was down to their efficient, concentrated geographical vote and tactical voting. In the 2024 election, their vote went up in seats where they were challenging the Conservatives but fell slightly in other seats. According to Chris Annous of More in Common, over a quarter (26%) of Liberal Democrat voters in 2024 said they had voted tactically. Data from the post-election British Election Study revealed that in seats where the Liberal Democrats were challenging the Conservatives, half of 2019 Labour voters, who had become more positive towards the Lib Dems, switched their vote to help the party defeat the incumbent Tory MP. My latest book Collapse of the Conservatives : Volatile Voters, Broken Britain and a Punishment Election is now available on Amazon.

The success of targeted, efficient vote strategies and increased tactical voting meant the conversion of votes to seats in the 2024 general election was highly disproportional. Reform UK won 4.1m votes, representing 14.3% of votes cast, but only won 5 seats. This was just one seat for every 820,000 votes it had received. Compare this to the efficiency of the Labour vote, where the party won one seat for every 23,000 votes received. The problem for Reform UK was that its four million votes were spread evenly and inefficiently across the country. Heinz Brandenburg, a University of Strathclyde political scientist, analysed the election using the Gallagher Index (the standard measure academics use to describe disproportionality) and found the 2024 election scored 24 on the Gallagher Index, beating the previous record of 21 in 1931. Thus, statistically, the 2024 election was the most disproportional electoral outcome in British electoral history. Dylan Difford looked at other measures of disproportionality, such as Loosemore-Hanby and Sainte-Lague indexes, and also found the result to be the least proportional in British election history, commenting, “However you assess it, this election was so extremely disproportional that it is an outlier by western democratic standards, let alone UK ones.” Robert Peston was quick to emphasise that it was the least proportional distribution of seats in modern electoral history. He commented, “If you believe that the configuration of the Commons should roughly reflect the revealed preferences of voters, this is not a fair result.” John Curtice also observed that “Labour’s strength in the new House of Commons is a heavily exaggerated reflection of the party’s limited popularity in the country.” Under the first-past-the-post system, whether a party wins a seat by a single vote or ten thousand votes doesn’t matter in terms of seats won. As Lewis Goodall observed, “Voter efficiency is everything in the British system. If you master that you win.” While this is obviously true the level of disproportionality raises questions about the electoral system and may provoke further discussion of electoral reform. My latest book Collapse of the Conservatives : Volatile Voters, Broken Britain and a Punishment Election is now available on Amazon.

The Labour Party won 411 seats in the 2024 general election, giving them a landslide majority of 174, the second-largest Labour majority since Blair’s victory in 1997. The party won back almost all of the Red Wall seats they had previously lost and gained nearly 40 seats from the SNP. It was a crushing victory for Keir Starmer and the Labour Party. On election night, Gary Gibbon, Channel 4’s political editor, was checking over the results as they came in. While other commentators were waxing lyrical about the scale of Labour’s victory, Gibbon raised his head and said it looks like a ‘loveless landslide’.

The reason for Gibbon’s comment was Labour’s apparently low share of the vote. By the following day it was clear that Labour had won just 34% of the votes cast. This was only marginally higher than Corbyn achieved in 2019 and a full six points below the party’s performance in 2017. John Curtice commented, “Never before has a party been able to form a majority government on so low a share of the vote.” The small increase in Labour’s share of the vote in 2024 was entirely the result of a 17-point increase in support for the party in Scotland. The Labour Party’s vote share in England did not increase at all from 2019. In Wales, the party's vote actually fell back by four points.

In the Red Wall, the Reform Party split the Conservative vote, allowing Labour to win back 39 of the 40 seats it lost in 2019, despite winning fewer votes than in the previous election. In terms of vote share, the party's vote was up across the 40 seats but only by 3.5% on average. In 11 seats, the party's vote share was actually lower than when they lost the seats in 2019. In Burnley, Hyndburn, and Bolton North East, Labour won back the seats despite a decline in their vote share of more than five points. A post-election analysis by More in Common found that if voters had voted with their heart rather than their head and not voted for Labour tactically, the support for Labour would have been four points lower and the Greens three points higher. Analysis of data from the post-election British Election Study found that 500,000 Labour voters voted tactically for the Liberal Democrats, but that was matched by the same number of Liberal Democrat voters who voted tactically for Labour. Labour finished just 10 points ahead of the Conservatives rather than the 19 to 20 points many of the polls predicted. The overestimation of Labour’s support was the highest ever seen, and the overall margin of error was the worst since the 1992 election. The polls had overestimated the support for both Labour and Reform UK and underestimated Conservative and Liberal Democrat support.

In terms of the absolute number of votes, Labour won 12.88m votes in 2017 and 10.27m votes in 2019. However, in 2024 the party won just 9.7m votes, albeit on a lower turnout. The turnout for the election was seven points lower than in 2019, falling to just 59.8%. The second lowest since 1885, suggesting there had been no enthusiasm for the election or the party offerings. Lewis Goodall commented, “The public, in many cases, have either felt apathetic or disinclined to choose between what was put before them.” The Labour Party lost almost a third of its support from Black and Asian communities in the general election, falling from 64% to 46%. The party’s stance on Gaza was a factor in areas with large numbers of people who identify as Muslim. The party's vote was down on average by 20.7 points in seats where over 20% of the population identified as Muslim . Lewis Baston’s research found that “in the 21 seats where more than 30% of the population is Muslim, Labour’s share dropped by 29 points from an average of 65% in 2019 to 36% in 2024.”

Labour lost four of these seats to independent candidates (Blackburn, Leicester South, Dewsbury & Batley and Birmingham Perry Barr,) where voters appeared to object to the Party not taking a stronger stance in support of Palestinians and a ceasefire in Gaza. Five more Labour MPs nearly lost their seats from this backlash amongst pro-Palestine Muslim voters. Rushanara Al’s majority fell from 37,500 to 1,700, Shabana Mahmood’s from 28,600 to 3,400, Naz Shah’s from 27,000 to 707, Jess Phillips from 10,700 to 693, and Wes Streeting’s from 5,200 to 528.

Luke Tryl argued that these falls in vote share should not simply be attributed to Labour’s position on Gaza. In focus groups, he noted there was real frustration over Labour on Gaza but also a feeling that Labour took Muslim votes for granted and that the party had neglected their communities. Participants talked about a lack of opportunities, crime and the fact no one listened to them. While Gaza was at the forefront of the campaigns of Independent candidates, they were also seen as potential champions for their community who’d stand up for them. Thus, it was possible that Gaza was a trigger, but many in these communities had started to become disconnected from Labour. Tryl observed that “in an age of electoral volatility, traditional loyalties are no longer enough to mean a party can count on the votes of a particular group. Particularly if they feel neglected or taken for granted by that party.” Why was the Labour vote share so low? The extensive publication of polls before the election indicating a Labour landslide may have discouraged some voters on the basis that the result was a foregone conclusion. Professor Paula Surridge argued there was likely to be “a significant group who felt that victory was assured and so didn’t vote. ”This view is supported by research evidence that significant poll leads can depress turnout, as voters believe their vote will change little in such situations. However, according to More in Common , just 4% of non-voters stayed at home because they were sure that the party they supported was going to win.

In the 63 safest Labour seats, the party’s average vote share decreased by 17% from 67% to 50%, and the party lost votes in most of the seats where they had won over 50% of the vote in 2019. The party only made gains in seats where their previous vote share was less than 50% in 2019. Labour strategists put this down to the party’s ruthless targeting of resources outside its core heartlands, so that its vote became more efficient, allowing it to win where it needed to and avoiding piling up votes in safe Labour seats.

It might also have been that many voters in Labour seats with large majorities felt able to vote for other parties, such as the Greens. If the election had been closer or Labour was at risk of losing these seats, the Labour vote might have been higher. As mentioned above, it might be that many Labour voters voted tactically for the Liberal Democrats in seats where they were the main challengers to the Conservatives, which depressed the Labour vote. However, the evidence suggests that just as many Liberal Democrats voted tactically for Labour in seats where they were the main challengers to the Conservatives, which would have increased the Labour vote share. A Lord Ashcroft Poll found that 32% of those who voted Labour said they were voting Labour tactically to try and stop the party they liked least from winning.

Patrick McGuire, a political columnist for The Times, claimed the Labour Party’s ability to win a landslide majority on such a low vote share was the fruit of a political strategy that had “ruthlessly maximised the efficiency of the Labour vote.” This is true, but the Labour Party was also aided greatly by the broad spread of the Reform UK vote, which took votes away from the Conservatives across a great many seats, allowing Labour to win without increasing its share of the vote and, in 57 cases, even winning back seats with a lower vote share than in 2019. The fact Labour didn’t increase their vote, in percentage or absolute terms, when the Conservative government was so unpopular indicated the public was far from excited about Keir Starmer and the Labour Party. John Curtice claimed there was little enthusiasm for Labour, noting that while Starmer had made his party acceptable, he was “not even as popular as David Cameron was before 2010.” To Curtice the election result had been shaped by the failures of the Conservative Party. Rosa Prince, the Deputy UK Editor at Politico, agreed, “There is little doubt that this election was a loss for the Conservatives rather than Labour’s gain; there was no surge of enthusiasm for the party.” Paula Surridge argued that the desire to see the back of the Tories appeared to outweigh any considerations of policy or even “whether Labour will actually deliver much positive change.” When it was elected, the satisfaction rating for the new Labour government was -21, which was an improvement on the Sunak government. However, for Cameron’s government, it was +10, and for Blair’s government, it was +37. It took two years for Blair’s government to have a negative satisfaction rating.

Keir Starmer was one of the most unpopular opposition leaders to win an election. When he became Prime Minister, he had a popularity rating according to Ipsos of plus seven (37% satisfied, 30% dissatisfied). This was low by historical standards for new Prime Ministers. For example, Cameron’s was +30, Blair’s +60, and May’s +35. It might be that the collapse in trust in politicians over the last five years means that no party leader these days could be expected to reach the higher ratings of previous Prime Ministers. Thus, Starmer’s low ratings might simply reflect the current public distrust of politicians. In September, Starmer’s net popularity rating according to Ipsos fell to -14. Political analysts disagree about the implications of the election result and the fragility of Labour’s electoral position. Peter Kellner has set out why he thinks Labour should be nervous, while Professor Ben Ansell suggests that the weak position of the Tories helps to secure Labour’s electoral advantage, although he still refers to the party as walking a tightrope. The electoral landscape has become so volatile that only a fool would make predictions about the next election, but it is clear that Labour has a lot of work on its hands to secure and build on its 2024 electoral coalition. A report on how Labour won the election by Labour Together, sums up the challenge for Starmer and the party: “Labour must never take voters for granted. Indeed, it cannot, because many are simply giving Labour a chance. It must approach every day of governing in the knowledge that it will need to persuade voters again and again and again." My latest book Collapse of the Conservatives : Volatile Voters, Broken Britain and a Punishment Election is now available on Amazon.”

Political distrust is at an all-time high, and it’s reshaping the electoral landscape in unsettling and unpredictable ways. Political trust is generally high when people have confidence in their government and political leaders, and view them as trustworthy, fair, credible and competent. In Western democracies, politicians have tended to be more distrusted than trusted. Some experts argue that this “liberal distrust” is a good thing as it ensures accountability through an ongoing evaluation of the performance of political leaders. Some have even referred to this liberal distrust as the ‘guardian of democracy’. However, what we’re seeing now in the UK is a deeper and more concerning level of political distrust. Bertsou argues it is important not to conflate "liberal distrust" with political distrust, which, far from being beneficial, is a potentially damaging and destabilising force. He argues that political distrust is not merely a lack of trust where there is doubt and scepticism about the government’s intentions but a strong and settled belief in the untrustworthiness of political leaders. Hence, once the public becomes distrustful of a government or politicians more generally, it is hard to reverse this view.

There are three aspects to political distrust according to Bertsou. The first is based on evaluating the competence of political leaders and government. The second is based on unethical and untrustworthy conduct, which the public sees as wrong or unfair. Public perceptions of untrustworthiness, corruption, bribery and cronyism are all strongly associated with political distrust. The third is based on partisanship, where people are more likely to distrust politicians they disagree with. Bertsou argues that distrust which stems from the betrayal of a previously extended trust, can carry a strong moral judgement.

Political trust has been declining in the UK for several decades. This has been attributed to political scandals, such as the MPs expenses scandal in 2009, and the increasing prominence of cynical views about politicians. In 1986, 40% of people trusted the government to place the nation’s needs above the interests of their party. By 2010, this had halved to 20%.

(See NatCen report .) The British Social Attitudes Survey 2023 report found that “people’s trust in government and politicians, and their confidence in their systems of government, is as low now as it has ever been over the last 50 years, if not lower.” The report argued that the actions of the Conservative government, particularly contravening its own rules on COVID-19, had a corrosive effect on public trust. By August 2022, 76% of the public felt Boris Johnson was untrustworthy. While the figures improved for Rishi Sunak, two-thirds of the public (65%) believed he was untrustworthy. The percentage of people who trust the government to place the nation's needs above their party most of the time fell from 24% in 2021 to 14% in 2023. More dramatically, the percentage of the public that trusted politicians to tell the truth in a tight corner fell from a low of 12% to just 5%. (See NatCen report. )

A 2023 Ipsos survey found that people's trust in politicians had fallen to its lowest level in 40 years. Just 9% of people said they trusted politicians to tell the truth, making them the least trusted profession in Britain. According to Ipsos, almost all of the decline in trust in Britain’s politicians over recent decades had come about during the Conservative Parliament of 2019 to 2024. In 2024, Ipsos conducted a study called ‘The People Behind the Polls’, where they followed a group of people during the 2024 election campaign and obtained their reactions to events such as the TV debates. This qualitative research survey found that the public had a “ complete distrust of politics and politicians. ” An analysis of the British Election Study panel in 2024 found that over 70% of those aged 18-60 agreed that ‘politicians don’t care what people like me think’. The figure was 76% for respondents aged 30-44. After participating in numerous focus groups the pollster, Luke Tryl, has claimed the public overwhelmingly distrust politicians of all parties. They either think they are not up to the job or are only in it for themselves. He believes the notion that there is one rule for politicians and another for other people “is toxic not just to one party but faith in politics itself.” (See Luke's posts here and here .) The 41st British Social Attitudes Report published on 12 June 2024 reported that public trust in government has fallen further to a new record low. Almost half of people said they would ‘almost never’ trust British governments of any party to place the country's needs above the interests of their own political party, more than ever before.

When non-voters were asked why they didn’t vote in 2024, the top answer selected by 34% was ‘I don’t trust any politicians’. When Keir Starmer became Labour leader, most of the public (59%) had no view on his trustworthiness, and only 19% distrusted him. However, the more the public got to see Starmer, the more they distrusted him. When it was revealed that Sue Gray had been offered a job as Labour’s chief of staff, the percentage of the public who believed Starmer was untrustworthy jumped from 38% in April 2023 to 45% in May 2023. In September 2024, after a difficult summer, 47% believed Starmer was untrustworthy. The Consequences of High Levels of Political Distrust Higher levels of voter distrust can lead to more unstable electoral environments. Research by Voogd et al ., published in 2019, found evidence that low levels of trust undermine the formation of stable party preferences and stimulate volatility. They discovered that declining trust drives voters, particularly supporters of parties in government, to change their party preference. High levels of distrust also create opportunities for populist parties, which appeal to voters with simple solutions on the basis that the political and establishment elites cannot be trusted.

High levels of distrust can also lead to unpredictable behaviour where voters seek to punish existing political leaders by acting or voting in a contrary manner to register a protest against the existing government. Research by Okolikj et al. found that voters with high levels of distrust were more likely to vote for protest parties, even if such parties were far removed from their own ideological position, to express their distrust of politicians.

Distrust can also lead to people opting out of the political system, which can be reflected in low levels of voting and political engagement. The 2020 British Attitudes Survey found that turnout in the 2019 election was lower among people who said they almost never trusted the government. The same survey also found that 62% wanted a change in the current voting system and were “markedly more likely to have a populist outlook.”

In summary, the growing levels of political distrust in the UK over the last decades have increased the potential for electoral volatility, including greater polarisation (Boxell et al. 2020), support for populism (Henley 2018), and a decline in political participation (Repucci and Slipowitz 2021). In 2021, the IPPR warned that this growing distrust “can lead to a downward spiral of democratic decline, with voters disengaging, becoming polarised, or turning to populist leaders and causes." My latest book Collapse of the Conservatives : Volatile Voters, Broken Britain and a Punishment Election is now available on Amazon.

One of the most striking features of the 2024 election was the scale of anti-Conservative tactical voting. The willingness of voters to engage in tactical voting, combined with the ruthless focus of the Labour, Liberal Democrat and Green parties on their target seats, resulted in remarkably successful efficient vote strategies. The three parties won almost all their target seats by building anti-incumbent, tactical-voting alliances around a clear second-place candidate in a constituency. The success of these strategies may provide a template for challenger parties in future elections. Anti-incumbent tactical voting has been around for a long time. Back in 1997, the Conservative Cabinet Minister, Michael Portillo, lost his safe seat after Liberal Democrat voters chose to tactically vote for Labour to remove him. What was different in 2024 was the industrial scale of tactical voting. Rather than seeking to maximise their national vote share, the Labour, Liberal Democrat, and Green parties focused their resources on seats where they could establish themselves as the primary challenger and withdrew resources from seats where another party was better placed. A More Volatile Electorate Voters who are less attached to political parties are more likely to vote tactically or on a transactional basis. In the UK, voters have become increasingly detached from political parties and are prepared to switch their vote between elections. This has been linked to major political shocks, which caused voter realignments such as the Scottish Independence and Brexit referendums, and to growing levels of distrust in politicians. The increased willingness of voters to switch votes between parties in elections can be seen in recent elections, including the 2024 general election, where around 40% of electors voted for a different party than they had voted for in 2019. Voters have become far more willing to vote on a transactional rather than an ideological basis. For example, voting to ‘get Brexit done’, to stop Jeremy Corbyn or to unseat an incumbent Conservative, rather than because they ideologically support the party they voted for. In Waveney Valley in 2024, it was clear that voters got behind the Green candidate to remove the Conservative MP rather than because they supported the party’s policy of unilateral nuclear disarmament. Steve Akehurst, director of the research group Persuasion UK, has argued that younger voters, in particular, “are far more transactional and less attached to political parties than older generations.” Chris Hopkins, political research director at Savanta, argues that tactical voting is also on the rise because voters have become “increasingly sophisticated in understanding how in a first-past-the-post system, their vote can be as effective as possible.” People appear to be increasingly aware of how to make their vote count in a first-past-the-post system, most notably by trying to stop a candidate they dislike being elected.

Analysis by Professor Stephen Fisher suggested that Labour and Liberal Democrat supporters were more willing to vote tactically for each other in 2024 than in 2019. This was primarily because Liberal Democrat voters were not worried about Keir Starmer to the degree they were with Jeremy Corbyn. Steve Akehurst’s research also suggested that Labour supporters in traditionally Conservative seats were very transactional and particularly open to voting for the Liberal Democrats or the Green Party to unseat a Conservative MP. Before the election a poll by Best for Britain found that four out of ten voters (40 per cent) were prepared to vote tactically to remove a Conservative MP. The increased willingness of voters to vote tactically put the Conservatives at risk in a large swathe of seats, particularly those which became known as the Blue Wall. Early Warning Signs In 2021, the Conservatives lost the Chesham and Amersham by-election to the Liberal Democrats. It was a graduate-heavy, middle-class, and Remain-voting constituency that had always elected a Conservative MP since its creation in 1974. The Conservatives blamed concerns over HS2 and planning reform, but John Curtice called it “a warning to the Conservatives” that the Liberal Democrats could pick up the votes of middle-class voters. There was evidence of significant tactical voting as Labour voters turned to the Liberal Democrats to remove the Tories. The Labour vote consequently fell to 1.2%, its lowest-ever share of the vote in a Westminster election. Later, in 2021, the Liberal Democrats overturned a 23,000 Tory majority in North Shropshire on a 34% swing. Despite Labour having been second in the constituency in the 2019 general election, many of their voters decided to swing tactically behind the Liberal Democrats. The Labour vote fell from 22.1% in 2019 to 9.7% in 2021. In 2022, the Conservative Party lost the Tiverton and Honiton by-election. The Liberal Democrats overturned a majority of 24,239 with a 29.9% swing. Peter Kellner noted that the scale of anti-Conservative tactical voting was ferocious and warned that “ strategic anti-Conservative tactical voting could decide the next election.” In the 2023 local elections, the Conservative Party lost over a thousand seats, and Labour became the largest party in local government, overtaking the Tories for the first time since 2002. Notably, the Liberal Democrats and the Greens also did well. In the Financial Times , Robert Shrimsley noted a sharp increase in anti-Tory tactical voting, which had eroded Tory majorities, particularly in more affluent southern seats. Tactical Voting in the 2024 General Election In the 2024 general election, voters' determination to punish the Conservatives was so strong that they appeared willing to lend their support to whichever party was best placed to beat Conservative candidates. The key challenge for Labour, Liberal Democrat, and Green candidates was to establish themselves as the primary challengers to the Conservatives. The targeted approach of efficient vote strategies only works if parties focus on seats where they can establish themselves as the primary challenger to the incumbent. If a party can do this successfully, other challenger parties will likely redirect their resources to other seats, making it easier to build an anti-incumbent alliance. The parties used a combination of MRP polls, local election results, and previous election results to make the case that they were the main challengers. Those constituencies where a party felt confident in establishing itself as the primary challenger became priority target seats and received significant resources. The degree of ruthless, focused campaigning was unprecedented in 2024 as parties poured resources into their target seats. The natural consequence of these strategies was that Labour put minimal resource into Liberal Democrat target seats and vice-versa. Liberal Democrat party activists were encouraged to only campaign in their target seats and not in those Labour might win. An analysis by the Financial Times found that Labour had also told its members not to campaign in the 80 Liberal Democrat target seats. There were claims that Labour and the Liberal Democrats had done a secret deal not to put resources into challenging each other in their respective target seats. This was denied, but in many ways, it was an inevitable outcome of both parties' strong focus on their target seats. Parties did not want to waste resources in constituencies where another party had a better chance of mobilising a tactical voting alliance. The targeted, efficient vote strategies were incredibly successful. The Liberal Democrats and the Labour Party advanced most where they were the primary opponents to the Conservatives in winnable target seats. Where Labour was the primary challenger to the Conservatives, support for the party rose by six points, while support for the Liberal Democrats fell. By contrast, where the primary challenger to the Conservatives was the Liberal Democrats, their support rose by nine points compared to just one point nationally. An analysis of post-election British Electoral Study data revealed a very efficient swap of Labour and Liberal Democrat voters. 500,000 Liberal Democrat voters voted tactically for Labour, and 500,000 Labour voters voted tactically for the Liberal Democrats. In The Times , John Curtice observed that the scale of anti-Conservative tactical voting had been remarkable. While in The Guardian, Will Jennings referred to "intense tactical voting." The level of tactical voting resulted in huge swings against incumbent candidates, allowing Labour, the Liberal Democrats, and the Greens to win almost all of their target seats. The Greens won all four of their target seats, and the Liberal Democrats won 72 of their target seats, their highest total of MPs since 1923. The Liberal Democrats and Labour's share of the national vote only changed marginally, but both parties won significantly more seats. The Liberal Democrats increased their national vote share from 11.6% to 12.2% but gained 64 seats. The Labour Party increased its national vote share from 32.1% to 33.7% but gained 211 extra seats. Dr Anton Howes claimed that the 2024 election result showed the first-past-the-post system at its best, as tactical voting allowed the electorate “to mete out proper punishment” to the government. Implications for the Future The success of targeted, efficient vote strategies that leveraged the public’s willingness to vote tactically was remarkable in terms of winning seats. It will surely be a strategy that all parties consider adopting in the next general election. In 2024, the strategy worked because the public was angry at the Tories and wanted them out. Its success in future elections will depend on the degree to which the public is unhappy with the Labour government and the public’s willingness to lend their support to second-place candidates. For example, there is some evidence that people are not as willing to lend their vote to Reform UK as they were to lend their vote to the Liberal Democrats or Labour. Tactical voting may present a particular challenge to Labour if it becomes disliked over the course of the parliament. High levels of political distrust can also create problems for incumbent governments as they are likely to be blamed for events on their watch, particularly economic events. Thus, a recession or economic crisis can quickly undermine support for a governing party. The Liberal Democrats are second in only 27 constituencies, all of which are held by Conservative MPs, and it may be harder for them to mobilise a tactical voting alliance when the Conservatives are not in government. However, Reform UK are second in 98 constituencies, 89 of them to Labour. At the same time, the Greens are second to Labour in 40 constituencies. Robert Shrimsley has suggested that Farage and Reform UK will seek to use a more ruthless and targeted strategy to mobilise tactical voting alliances against Labour incumbents. The party’s former leader, Richard Tice, has already said they want to learn from the Liberal Democrats campaign . Will the success of Labour’s targeted campaign strategy in 2024, potentially be its undoing in the next election?

Above my desk I have a cork board that holds some of the badges I wore between 1978 and 1987. The badges were the inspiration for the title of my latest book: Badgeland. Political badges - or campaign buttons as they are known in the U.S. - were very common throughout the 1970s and 1980s. We wore our badges on our chests with pride like twelfth century pilgrims who bought pewter badges to demonstrate their devout status. Below is a brief summary of the badges which graced my denim jacket from 1978 to 1987.

If you are looking for advice as an Independent author I can really recommend the Two Indie Authors podcast. In this podcast the best-selling indie authors, David B. Lyons and Robert Enright talk about about being an independent author. I have found the podcast to be open, honest and refreshing. The authors cover a lot of ground including why they chose to be Indie authors, the tools they use (big shout out to Vellum), how they market their books and discuss numbers (including their costs and sales). The discussions are in-depth, each podcast is about an hour long and there are no adverts that you have fast forward through. Their episodes so far have covered: How they became full time authors How they market their books How they write their books The costs of self-publishing The numbers that matter, particularly advertising costs and returns What to include in your front and back matter Audiobooks In each episode they also interview experts and authors for their tips and advice on being an Indie author. What are you waiting for? Go check it out. Two Indie Authors