The Conservative Party's Four Key Challenges

Following her election on 2 November 2024, Kemi Badenoch and the Conservative Party face a number of key challenges:

• The Reform challenge

• The competence challenge

• The narrative challenge

• The demographic challenge

The Reform Challenge

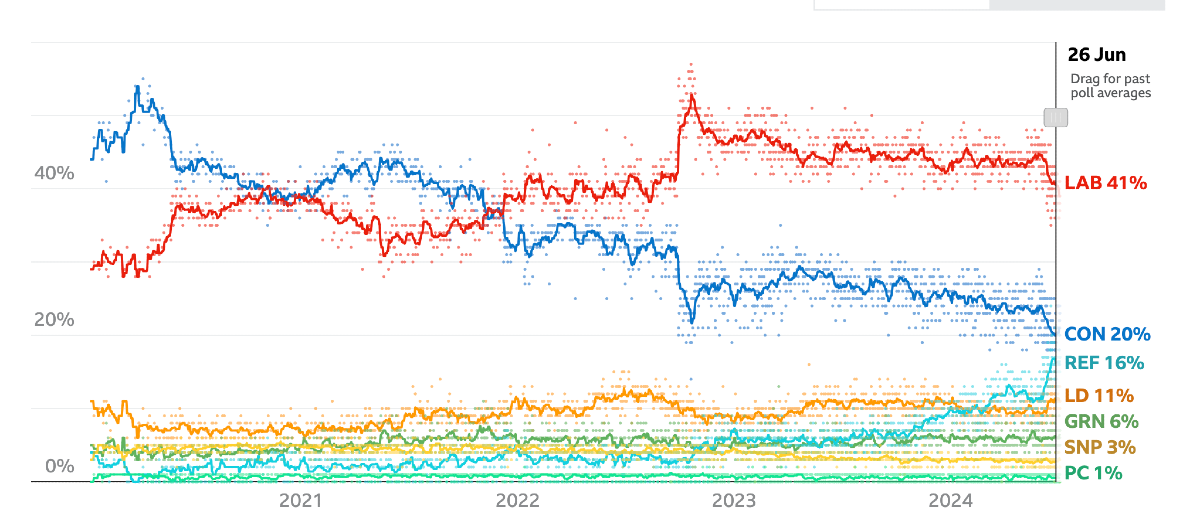

One reason the Conservatives dominated parliament over the last 80 years is that the country’s centre-right vote consolidated behind the party while the centre-left vote was divided between parties, primarily Labour and Liberal Democrats. The rise of Reform fatally divided the centre-right in 2024, making it easier for Labour to win seats from the Conservatives.

The threat from Farage and his colleagues is very real. Nearly a third (29%) of the Conservative Party’s 2024 voters said they had considered voting for Reform, compared to 17% who said they had considered voting for the Liberal Democrats.

Kemi Badenoch has said Nigel Farage would not be welcome in the party, saying, “We are a broad church but if somebody says they want to burn your church down, we don’t let them in.”

A YouGov survey after the election revealed that 42% of Conservative Party members would support a merger with Reform, while 51% would oppose such a move. Only 34% of party members felt the party should move to the centre with 51% believing the party should move to the right to attract Reform voters.

However, a survey by Savanta suggests that Tory to Reform switchers are probably the hardest voters for the party to win back.

The other problem is that even if the party could win back every vote that went to Reform in the general election and keep all of its 2024 voters, it would still only win 302 seats, which falls short of securing the 326 seats required for a bare majority in parliament.

If Reform does become increasingly professional, does more work building a base on the ground in constituencies, and develops a targeted approach to election campaigns, there is a risk that it could become an even greater threat to the Conservatives.

The Competence Challenge

After 2016, the Conservative Party lost its reputation for competence and lost the trust of key groups of voters. There is evidence that people primarily broke with the Conservatives over the issue of competence, but where they went depended on their values. So, more authoritarian voters went to Reform, while others went to Labour, the Liberal Democrats, or other parties, and others stayed at home.

A key challenge is how the party rebuilds its reputation for competence while in opposition. Some commentators have argued that voters become frustrated with governments and that if Labour begins to look incompetent, then the Conservatives will appear competent by comparison. Thus, time will solve some of the party’s problems. The difficulty with this argument is that the voters may desert Labour, but they may not return to the Conservatives. They may express their dissatisfaction with the government by voting for the Greens, independents, or Reform.

To rebuild trust and a reputation for competence, the party must be seen to be united under an effective leader. The leadership team also needs to exude capability and integrity. There needs to be a perception of discipline, not one of constant infighting between factions.

The party also needs to be honest about its own failings while in government. A 40-page pamphlet promoted by Kemi Badenoch as part of her leadership campaign, Conservatism in Crisis,1 was remarkable in failing to address why the Conservatives lost the election. There was no acknowledgement that the party presided over crumbling public services and was perceived as incompetent. The only reference was to the failure to control immigration; there was not a single mention of competence.

The Narrative Challenge

One of the Conservative Party’s key challenges is to define a new narrative or reclaim a previous narrative. Fundamentally, what does the party stand for?

Traditionally, the party has claimed to be the party of sound economic management, and a supporter of the free market, a smaller state, and lower taxes. Following the Truss debacle, it may take some time for the Conservative Party to recover its reputation as economically competent.

If the party is going to advocate for a smaller state, it needs to be clear what this means and the significant reductions in state activity it would like to see. The frequent cries for reductions in foreign aid, fewer regulations, and cuts in funding to arts organisations are too small to make any real difference to the level of state spending. The big spending areas, such as the NHS, schools, and local government, have already been cut heavily, and there appears little scope for further reductions. Indeed, the public in 2024 wanted to see more investment, not less, in these areas while accepting that there could be some scope for greater efficiency. Even the Conservative 2019 voters who defected to Reform wanted to see more investment in public spending and an improved NHS.

It is not clear the Conservatives have yet understood that the electorate is more supportive of state intervention and public services than they are.

In her pamphlet, Conservatism in Crisis, Kemi Badenoch argued that what all Conservatives want is “growth, social cohesion, better public services and sustainably lower taxes”. The potential dichotomy of lower taxes and better public services was not recognised. She argues that taxes can be cut significantly while at the same time improving public services. She believes this could be done by reducing regulation, cutting welfare spending, and making cuts in what she terms the bureaucratic class, primarily administrators such as human resources, equalities, and compliance staff.

All of the groups of voters the Conservatives lost in 2024 were to the left of the party on key economic issues, including Reform voters. These voters want to see more public service investment and are not instinctively small-state advocates. The centre-right think tank Onward argues the Conservatives will, therefore, have to craft a strong story that the party can manage and improve public services, particularly the NHS, which will mean a new triangulation around the issue of tax cuts and public spending.

The Demographic Challenge

The party’s voting base in 2024 was older than it had ever been. The only age group the Conservatives won in the election was the over-65-year-olds. On current trends, there is a real danger that the Conservative Party will become the pensioner party.

The country’s changing demographics will make it increasingly difficult for the party to win unless they can increase their appeal to younger people. Focaldata has estimated that some 17%, or one in six of those who voted Conservative in 2024, will have died by the time of the next election. That would mean over a million fewer Tory voters lost solely as a result of demography. By contrast, the Labour Party is anticipated to gain the support of 800,000 young people who become legally able to vote before the next election, compared to just 160,000 for the Conservatives. If Labour legislates to grant the vote to 16 and 17-year-olds as they intend, the position is likely to get worse for the Conservatives.

Young people’s perceptions of the Tories declined markedly after Brexit. The percentage of 18 to 34-year-olds saying they strongly disliked the Conservative Party jumped from around 20% prior to the Brexit referendum to over 40% by 2023.

This was the age group that Thatcher successfully appealed to in the 1980s. Her policies, including lower taxes, ‘right to buy’, and the sale of shares in previously nationalised industries, were designed to appeal to young aspirational voters and encourage social mobility. In 1979, 42% of 18 to 24-year-olds and 43% of 25 to 34-year-olds voted for the Conservative Party. In 2024, the party secured just 5% of the votes of 18 to 24-year-olds and 10% of the votes of 25 to 34-year-olds. The party came fifth amongst this younger age group, behind Labour, the Greens, the Liberal Democrats and Reform.

The Conservative Party has arguably been too focused on maintaining the support of the older generation of homeowners and become detached from the aspirations and values of the next generation. This matters because the party can no longer rely on the traditional conservatising effect of age, which was observable in previous generations as voters became homeowners, got married, and had children.

Britain’s younger generation overwhelmingly voted for the stability of remaining in Europe and are particularly frustrated at the broken housing market. Like the previous generations, they aspire to own their own homes but find it increasingly difficult as house prices and rents have increased relative to salaries.

The Conservative Party’s problems with younger voters are stark. Sam Freedman has observed that the real challenge for the Conservatives is “finding a way to reconnect with younger and middle-aged people earning, or hoping to earn, decent salaries and own a home”.

For the Conservative Party to win again, it needs to find a way to appeal to young, aspirational, and socially liberal voters.

My latest book Collapse of the Conservatives : Volatile Voters, Broken Britain and a Punishment Election is now available on Amazon.