Election 2024: Tactical Voting and the Success of Targeted Campaigns

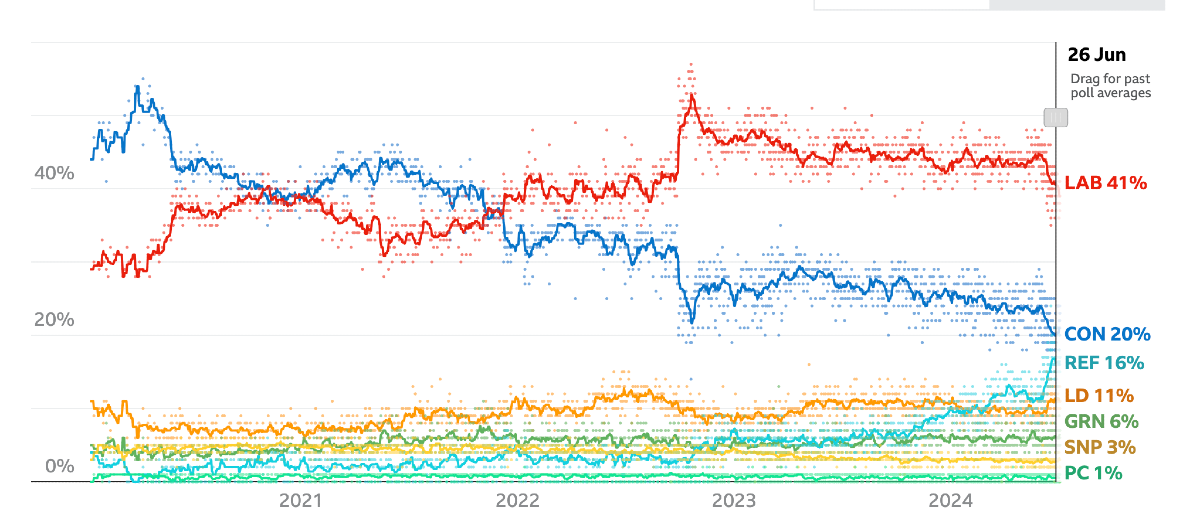

One of the most striking features of the 2024 election was the scale of anti-Conservative tactical voting. The willingness of voters to engage in tactical voting, combined with the ruthless focus of the Labour, Liberal Democrat and Green parties on their target seats, resulted in remarkably successful efficient vote strategies. The three parties won almost all their target seats by building anti-incumbent, tactical-voting alliances around a clear second-place candidate in a constituency. The success of these strategies may provide a template for challenger parties in future elections.

Anti-incumbent tactical voting has been around for a long time. Back in 1997, the Conservative Cabinet Minister, Michael Portillo, lost his safe seat after Liberal Democrat voters chose to tactically vote for Labour to remove him. What was different in 2024 was the industrial scale of tactical voting. Rather than seeking to maximise their national vote share, the Labour, Liberal Democrat, and Green parties focused their resources on seats where they could establish themselves as the primary challenger and withdrew resources from seats where another party was better placed.

A More Volatile Electorate

Voters who are less attached to political parties are more likely to vote tactically or on a transactional basis. In the UK, voters have become increasingly detached from political parties and are prepared to switch their vote between elections. This has been linked to major political shocks, which caused voter realignments such as the Scottish Independence and Brexit referendums, and to growing levels of distrust in politicians.

The increased willingness of voters to switch votes between parties in elections can be seen in recent elections, including the 2024 general election, where around 40% of electors voted for a different party than they had voted for in 2019.

Voters have become far more willing to vote on a transactional rather than an ideological basis. For example, voting to ‘get Brexit done’, to stop Jeremy Corbyn or to unseat an incumbent Conservative, rather than because they ideologically support the party they voted for. In Waveney Valley in 2024, it was clear that voters got behind the Green candidate to remove the Conservative MP rather than because they supported the party’s policy of unilateral nuclear disarmament.

Steve Akehurst, director of the research group Persuasion UK, has argued that younger voters, in particular,

“are far more transactional and less attached to political parties than older generations.” Chris Hopkins, political research director at Savanta, argues that tactical voting is also on the rise because voters have become

“increasingly sophisticated in understanding how in a first-past-the-post system, their vote can be as effective as possible.” People appear to be increasingly aware of how to make their vote count in a first-past-the-post system, most notably by trying to stop a candidate they dislike being elected.

Analysis by Professor Stephen Fisher suggested that Labour and Liberal Democrat supporters were more willing to vote tactically for each other in 2024 than in 2019. This was primarily because Liberal Democrat voters were not worried about Keir Starmer to the degree they were with Jeremy Corbyn.

Steve Akehurst’s research also suggested that Labour supporters in traditionally Conservative seats were very transactional and particularly open to voting for the Liberal Democrats or the Green Party to unseat a Conservative MP. Before the election a

poll by Best for Britain found that four out of ten voters (40 per cent) were prepared to vote tactically to remove a Conservative MP.

The increased willingness of voters to vote tactically put the Conservatives at risk in a large swathe of seats, particularly those which became known as the Blue Wall.

Early Warning Signs

In 2021, the Conservatives lost the Chesham and Amersham by-election to the Liberal Democrats. It was a graduate-heavy, middle-class, and Remain-voting constituency that had always elected a Conservative MP since its creation in 1974. The Conservatives blamed concerns over HS2 and planning reform, but John Curtice called it “a warning to the Conservatives” that the Liberal Democrats could pick up the votes of middle-class voters. There was evidence of significant tactical voting as Labour voters turned to the Liberal Democrats to remove the Tories. The Labour vote consequently fell to 1.2%, its lowest-ever share of the vote in a Westminster election.

Later, in 2021, the Liberal Democrats overturned a 23,000 Tory majority in North Shropshire on a 34% swing. Despite Labour having been second in the constituency in the 2019 general election, many of their voters decided to swing tactically behind the Liberal Democrats. The Labour vote fell from 22.1% in 2019 to 9.7% in 2021.

In 2022, the Conservative Party lost the Tiverton and Honiton by-election. The Liberal Democrats overturned a majority of 24,239 with a 29.9% swing. Peter Kellner noted that the scale of anti-Conservative tactical voting was ferocious and warned that “strategic anti-Conservative tactical voting could decide the next election.”

In the 2023 local elections, the Conservative Party lost over a thousand seats, and Labour became the largest party in local government, overtaking the Tories for the first time since 2002. Notably, the Liberal Democrats and the Greens also did well. In the

Financial Times, Robert Shrimsley noted a sharp increase in anti-Tory tactical voting, which had eroded Tory majorities, particularly in more affluent southern seats.

Tactical Voting in the 2024 General Election

In the 2024 general election, voters' determination to punish the Conservatives was so strong that they appeared willing to lend their support to whichever party was best placed to beat Conservative candidates. The key challenge for Labour, Liberal Democrat, and Green candidates was to establish themselves as the primary challengers to the Conservatives.

The targeted approach of efficient vote strategies only works if parties focus on seats where they can establish themselves as the primary challenger to the incumbent. If a party can do this successfully, other challenger parties will likely redirect their resources to other seats, making it easier to build an anti-incumbent alliance. The parties used a combination of MRP polls, local election results, and previous election results to make the case that they were the main challengers.

Those constituencies where a party felt confident in establishing itself as the primary challenger became priority target seats and received significant resources. The degree of ruthless, focused campaigning was unprecedented in 2024 as parties poured resources into their target seats. The natural consequence of these strategies was that Labour put minimal resource into Liberal Democrat target seats and vice-versa. Liberal Democrat party activists were encouraged to only campaign in their target seats and not in those Labour might win. An analysis by the

Financial Times found that Labour had also told its members not to campaign in the 80 Liberal Democrat target seats. There were claims that Labour and the Liberal Democrats had done a secret deal not to put resources into challenging each other in their respective target seats. This was denied, but in many ways, it was an inevitable outcome of both parties' strong focus on their target seats. Parties did not want to waste resources in constituencies where another party had a better chance of mobilising a tactical voting alliance.

The targeted, efficient vote strategies were incredibly successful. The Liberal Democrats and the Labour Party advanced most where they were the primary opponents to the Conservatives in winnable target seats. Where Labour was the primary challenger to the Conservatives, support for the party rose by six points, while support for the Liberal Democrats fell. By contrast, where the primary challenger to the Conservatives was the Liberal Democrats, their support rose by nine points compared to just one point nationally.

An

analysis of post-election British Electoral Study data revealed a very efficient swap of Labour and Liberal Democrat voters. 500,000 Liberal Democrat voters voted tactically for Labour, and 500,000 Labour voters voted tactically for the Liberal Democrats.

In

The Times, John Curtice observed that the scale of anti-Conservative tactical voting had been remarkable. While in The Guardian, Will Jennings referred to "intense tactical voting." The level of tactical voting resulted in huge swings against incumbent candidates, allowing Labour, the Liberal Democrats, and the Greens to win almost all of their target seats. The Greens won all four of their target seats, and the Liberal Democrats won 72 of their target seats, their highest total of MPs since 1923.

The Liberal Democrats and Labour's share of the national vote only changed marginally, but both parties won significantly more seats. The Liberal Democrats increased their national vote share from 11.6% to 12.2% but gained 64 seats. The Labour Party increased its national vote share from 32.1% to 33.7% but gained 211 extra seats.

Dr Anton Howes claimed that the 2024 election result showed the first-past-the-post system at its best, as tactical voting allowed the electorate

“to mete out proper punishment” to the government.

Implications for the Future

The success of targeted, efficient vote strategies that leveraged the public’s willingness to vote tactically was remarkable in terms of winning seats. It will surely be a strategy that all parties consider adopting in the next general election. In 2024, the strategy worked because the public was angry at the Tories and wanted them out. Its success in future elections will depend on the degree to which the public is unhappy with the Labour government and the public’s willingness to lend their support to second-place candidates. For example, there is some evidence that people are not as willing to lend their vote to Reform UK as they were to lend their vote to the Liberal Democrats or Labour.

Tactical voting may present a particular challenge to Labour if it becomes disliked over the course of the parliament. High levels of political distrust can also create problems for incumbent governments as they are likely to be blamed for events on their watch, particularly economic events. Thus, a recession or economic crisis can quickly undermine support for a governing party.

The Liberal Democrats are second in only 27 constituencies, all of which are held by Conservative MPs, and it may be harder for them to mobilise a tactical voting alliance when the Conservatives are not in government. However, Reform UK are second in 98 constituencies, 89 of them to Labour. At the same time, the Greens are second to Labour in 40 constituencies. Robert Shrimsley has suggested that Farage and Reform UK will seek to use a more ruthless and targeted strategy to mobilise tactical voting alliances against Labour incumbents. The party’s former leader, Richard Tice, has already said

they want to learn from the Liberal Democrats campaign.

Will the success of Labour’s targeted campaign strategy in 2024, potentially be its undoing in the next election?