21 September 2024

The Labour Party won 411 seats in the 2024 general election, giving them a landslide majority of 174, the second-largest Labour majority since Blair’s victory in 1997. The party won back almost all of the Red Wall seats they had previously lost and gained nearly 40 seats from the SNP. It was a crushing victory for Keir Starmer and the Labour Party. On election night, Gary Gibbon, Channel 4’s political editor, was checking over the results as they came in. While other commentators were waxing lyrical about the scale of Labour’s victory, Gibbon raised his head and said it looks like a ‘loveless landslide’.

The reason for Gibbon’s comment was Labour’s apparently low share of the vote. By the following day it was clear that Labour had won just 34% of the votes cast. This was only marginally higher than Corbyn achieved in 2019 and a full six points below the party’s performance in 2017. John Curtice commented, “Never before has a party been able to form a majority government on so low a share of the vote.” The small increase in Labour’s share of the vote in 2024 was entirely the result of a 17-point increase in support for the party in Scotland. The Labour Party’s vote share in England did not increase at all from 2019. In Wales, the party's vote actually fell back by four points.

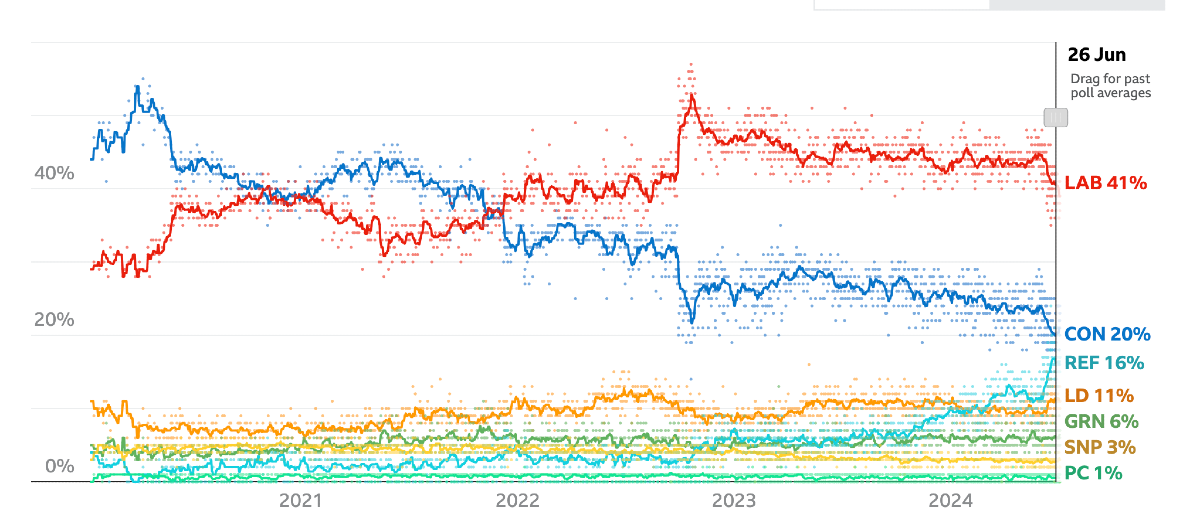

In the Red Wall, the Reform Party split the Conservative vote, allowing Labour to win back 39 of the 40 seats it lost in 2019, despite winning fewer votes than in the previous election. In terms of vote share, the party's vote was up across the 40 seats but only by 3.5% on average. In 11 seats, the party's vote share was actually lower than when they lost the seats in 2019. In Burnley, Hyndburn, and Bolton North East, Labour won back the seats despite a decline in their vote share of more than five points. A post-election analysis by More in Common found that if voters had voted with their heart rather than their head and not voted for Labour tactically, the support for Labour would have been four points lower and the Greens three points higher. Analysis of data from the post-election British Election Study found that 500,000 Labour voters voted tactically for the Liberal Democrats, but that was matched by the same number of Liberal Democrat voters who voted tactically for Labour. Labour finished just 10 points ahead of the Conservatives rather than the 19 to 20 points many of the polls predicted. The overestimation of Labour’s support was the highest ever seen, and the overall margin of error was the worst since the 1992 election. The polls had overestimated the support for both Labour and Reform UK and underestimated Conservative and Liberal Democrat support.

In terms of the absolute number of votes, Labour won 12.88m votes in 2017 and 10.27m votes in 2019. However, in 2024 the party won just 9.7m votes, albeit on a lower turnout. The turnout for the election was seven points lower than in 2019, falling to just 59.8%. The second lowest since 1885, suggesting there had been no enthusiasm for the election or the party offerings. Lewis Goodall commented, “The public, in many cases, have either felt apathetic or disinclined to choose between what was put before them.” The Labour Party lost almost a third of its support from Black and Asian communities in the general election, falling from 64% to 46%. The party’s stance on Gaza was a factor in areas with large numbers of people who identify as Muslim. The party's vote was down on average by 20.7 points in seats where over 20% of the population identified as Muslim . Lewis Baston’s research found that “in the 21 seats where more than 30% of the population is Muslim, Labour’s share dropped by 29 points from an average of 65% in 2019 to 36% in 2024.”

Labour lost four of these seats to independent candidates (Blackburn, Leicester South, Dewsbury & Batley and Birmingham Perry Barr,) where voters appeared to object to the Party not taking a stronger stance in support of Palestinians and a ceasefire in Gaza. Five more Labour MPs nearly lost their seats from this backlash amongst pro-Palestine Muslim voters. Rushanara Al’s majority fell from 37,500 to 1,700, Shabana Mahmood’s from 28,600 to 3,400, Naz Shah’s from 27,000 to 707, Jess Phillips from 10,700 to 693, and Wes Streeting’s from 5,200 to 528.

Luke Tryl argued that these falls in vote share should not simply be attributed to Labour’s position on Gaza. In focus groups, he noted there was real frustration over Labour on Gaza but also a feeling that Labour took Muslim votes for granted and that the party had neglected their communities. Participants talked about a lack of opportunities, crime and the fact no one listened to them. While Gaza was at the forefront of the campaigns of Independent candidates, they were also seen as potential champions for their community who’d stand up for them. Thus, it was possible that Gaza was a trigger, but many in these communities had started to become disconnected from Labour. Tryl observed that “in an age of electoral volatility, traditional loyalties are no longer enough to mean a party can count on the votes of a particular group. Particularly if they feel neglected or taken for granted by that party.” Why was the Labour vote share so low? The extensive publication of polls before the election indicating a Labour landslide may have discouraged some voters on the basis that the result was a foregone conclusion. Professor Paula Surridge argued there was likely to be “a significant group who felt that victory was assured and so didn’t vote. ”This view is supported by research evidence that significant poll leads can depress turnout, as voters believe their vote will change little in such situations. However, according to More in Common , just 4% of non-voters stayed at home because they were sure that the party they supported was going to win.

In the 63 safest Labour seats, the party’s average vote share decreased by 17% from 67% to 50%, and the party lost votes in most of the seats where they had won over 50% of the vote in 2019. The party only made gains in seats where their previous vote share was less than 50% in 2019. Labour strategists put this down to the party’s ruthless targeting of resources outside its core heartlands, so that its vote became more efficient, allowing it to win where it needed to and avoiding piling up votes in safe Labour seats.

It might also have been that many voters in Labour seats with large majorities felt able to vote for other parties, such as the Greens. If the election had been closer or Labour was at risk of losing these seats, the Labour vote might have been higher. As mentioned above, it might be that many Labour voters voted tactically for the Liberal Democrats in seats where they were the main challengers to the Conservatives, which depressed the Labour vote. However, the evidence suggests that just as many Liberal Democrats voted tactically for Labour in seats where they were the main challengers to the Conservatives, which would have increased the Labour vote share. A Lord Ashcroft Poll found that 32% of those who voted Labour said they were voting Labour tactically to try and stop the party they liked least from winning.

Patrick McGuire, a political columnist for The Times, claimed the Labour Party’s ability to win a landslide majority on such a low vote share was the fruit of a political strategy that had “ruthlessly maximised the efficiency of the Labour vote.” This is true, but the Labour Party was also aided greatly by the broad spread of the Reform UK vote, which took votes away from the Conservatives across a great many seats, allowing Labour to win without increasing its share of the vote and, in 57 cases, even winning back seats with a lower vote share than in 2019. The fact Labour didn’t increase their vote, in percentage or absolute terms, when the Conservative government was so unpopular indicated the public was far from excited about Keir Starmer and the Labour Party. John Curtice claimed there was little enthusiasm for Labour, noting that while Starmer had made his party acceptable, he was “not even as popular as David Cameron was before 2010.” To Curtice the election result had been shaped by the failures of the Conservative Party. Rosa Prince, the Deputy UK Editor at Politico, agreed, “There is little doubt that this election was a loss for the Conservatives rather than Labour’s gain; there was no surge of enthusiasm for the party.” Paula Surridge argued that the desire to see the back of the Tories appeared to outweigh any considerations of policy or even “whether Labour will actually deliver much positive change.” When it was elected, the satisfaction rating for the new Labour government was -21, which was an improvement on the Sunak government. However, for Cameron’s government, it was +10, and for Blair’s government, it was +37. It took two years for Blair’s government to have a negative satisfaction rating.

Keir Starmer was one of the most unpopular opposition leaders to win an election. When he became Prime Minister, he had a popularity rating according to Ipsos of plus seven (37% satisfied, 30% dissatisfied). This was low by historical standards for new Prime Ministers. For example, Cameron’s was +30, Blair’s +60, and May’s +35. It might be that the collapse in trust in politicians over the last five years means that no party leader these days could be expected to reach the higher ratings of previous Prime Ministers. Thus, Starmer’s low ratings might simply reflect the current public distrust of politicians. In September, Starmer’s net popularity rating according to Ipsos fell to -14. Political analysts disagree about the implications of the election result and the fragility of Labour’s electoral position. Peter Kellner has set out why he thinks Labour should be nervous, while Professor Ben Ansell suggests that the weak position of the Tories helps to secure Labour’s electoral advantage, although he still refers to the party as walking a tightrope. The electoral landscape has become so volatile that only a fool would make predictions about the next election, but it is clear that Labour has a lot of work on its hands to secure and build on its 2024 electoral coalition. A report on how Labour won the election by Labour Together, sums up the challenge for Starmer and the party: “Labour must never take voters for granted. Indeed, it cannot, because many are simply giving Labour a chance. It must approach every day of governing in the knowledge that it will need to persuade voters again and again and again." My latest book Collapse of the Conservatives : Volatile Voters, Broken Britain and a Punishment Election is now available on Amazon.”